“What an astonishing book this is!”

—Rosemary Mahoney, author of Down the Nile: Alone in a Fisherman’s Skiff

“… This is a unique and captivating view of the world, from 1919 to 1937, from a beautiful and memorable woman whose playfulness with words makes this great fun to read!”

—Rita Golden Gelman, author of Tales of a Female Nomad: Living at Large in the World

Summary

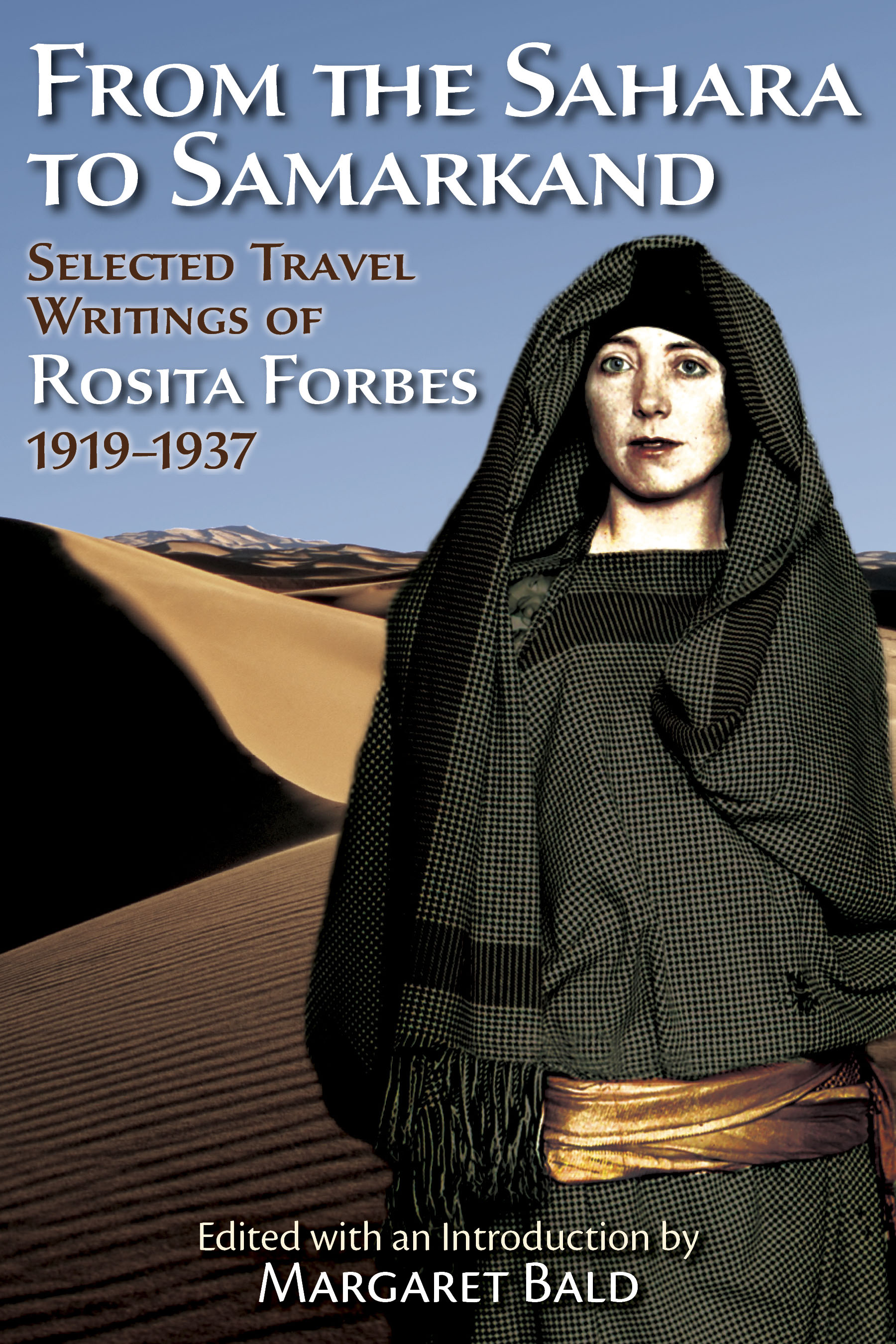

In the 1920s and ’30s, the extraordinary Rosita Forbes explored the Libyan desert, sailed across the Red Sea to Yemen, trekked more than a thousand miles into remote Abyssinia, and traveled in Southeast Asia and China, Morocco, Turkey, Iraq, Persia, and Afghanistan. She wrote some thirty books about these and other journeys, was a widely published journalist, a documentary filmmaker, and the editor of a pioneering women’s magazine.

Forbes was also a Jazz Age style icon, known as much for her glamour and charm as for her splendid adventures and the engaging and insightful books she wrote about them. This is the first anthology of her travel writing.

“In real life, the big things and the little things are inextricably mixed up together, so in Libya at one moment, one worried because one’s native boots were full of holes, and at the next, perhaps, one wondered how long one would be alive to wear them.”

—Rosita Forbes

About the Editor

Margaret Bald is the author of Banned Books: Literature Suppressed on Religious Grounds and the co-author of 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature and 100 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature. She has been a freelance journalist and foreign correspondent, an editorial consultant to the United Nations, managing editor of World Press Review Magazine, and publications director at the social policy research organization MDRC. She lives with her family in Brooklyn, New York.

Kay Hardy Campbell (Saudi Aramco World, March/April 2012):

“Rosita Forbes is a name most modern readers will not recognize. In the 1920s and 1930s, however, she was one of the world’s most popular travel writers, venturing to remote destinations in the Middle and Far East, often in disguise, often in search of legendary places rarely visited by westerners. She was a daring and colorful personality, known to royalty yet willing to ride mules, camels and broken-down jalopies to reach her destinations. Forbes penned 30 books, all now out of print. This book holds 32 of her travel stories describing fascinating places she visited, many of which have been forever altered by modernity. In addition, Forbes provided invaluable descriptions of women she met. She also noted, but barely complained about, insect scourges, bad weather, treacherous guides and poor housing conditions. Her stories retain many archaic place names, so readers will need to consult geographic references, adding to the charm of exploring this collection.”

Deborah Manley (ASTENE Bulletin, Autumn 2011):

“Living women explorer-travellers support this book with great enthusiasm. . . . With Rosita Forbes’ books long out of print, Margaret Bald has done a great service, to her and to us, in bringing out this book. Many of us will need to take to the second-hand bookshops or our libraries to search out her other books once we have absorbed this excellent starter.”

[Complete review (see pg. 12): Astene.org.uk]

Deborah Manley (ASTENE Bulletin, Winter 2010-11):

“[Rosita Forbes] published two autobiographies and a dozen books about her travels in the Pacific, the Sahara, Abyssinia, Afghanistan, South America, Samarkand, India and the Bahamas. . . . Indeed, this book is a series of adventures—many of them in ASTENE-land—and I was delighted to be introduced to it.”

[Complete review (see pg. 13): Astene.org.uk]

Joshua Hammer (The New York Times, Sunday Book Review):

Almost a century ago, Rosita Forbes, the bride of an adulterous Scottish army officer, pawned her wedding ring, bought a horse, a revolver, and a camera and embarked on what would be a long, adventurous career as a travel writer…. Margaret Bald provides a taste of some of Forbes’s forays into the Libyan Desert, Iraq, Afghanistan and a disintegrating, post-World War I China…. Best… is the story of her attempted pilgrimage to Mecca in August 1922. Swathed in a shapeless black abaya, she identifies herself as half Turk, half Egyptian and sets out with hundreds of Muslim pilgrims on a boat sailing across the Red Sea from Egypt to Saudi Arabia.

[Complete review: NYTimes.com]

Lois Henderson (BookPleasures.com):

“[Rosita Forbes’s] incredible courage, with her apparent implacability in the face of often daunting odds . . . has one spellbound from start to finish of this remarkable anthology. . . . An inspiring volume for modern-day travelers, whether of the armchair variety or of the more adventurous kind, this book is not to be missed.”

[Complete review: BookPleasures.com]

From the Sahara to Samarkand is featured in the Literature & Travel section of the Fall 2010 issue of The Bloomsbury Review:

Patricia Dubrava (The Bloomsbury Review):

“From the Sahara to Samarkand is the first anthology of [Rosita Forbes’s] travel writings to be published. It includes selections from eight of her travel books…a thorough and enthusiastic introduction to her life and work, and a photo gallery.”

Midwest Book Review:

“A choice addition to any literary collection focusing on travel writing.”

[Complete review: MidwestBookReview.com]

Hrayr Berberoglu (Wine’s World Blog):

“This is a book to read, enjoy, imagine the difficulties [Rosita Forbes] encountered, and problems she had to solve, and discuss with like-minded friends. Highly recommended!”

National Geographic Traveler, August 2010

[Traveler.NationalGeographic.com]

Jim Agnew Daily Pick, August 31, 2010

Praise for: From the Sahara to Samarkand

Rosemary Mahoney (author of Down the Nile: Alone in a Fisherman’s Skiff):

“What an astonishing book this is! Rosita Forbes was not just intrepid but extremely intelligent, not just adventurous but deeply curious, not just a fine writer but a shrewd and sympathetic observer as well. It’s rare to find a person at once so iconoclastic, unconventional and fearless and yet so attuned to her fellow human beings across the globe.”

Rita Golden Gelman (author of Tales of a Female Nomad: Living at Large in the World):

“Oh, how captivating are the details of her descriptions, the gutsiness of her adventures, her disguises and lies as she moves through mostly Arabic/Islamic worlds where the English are unwelcome, women are hidden, and amenities are rare! Even with a whiff of colonialism, this is a unique and captivating view of the world, from 1919 to 1937, from a beautiful and memorable woman whose playfulness with words makes this great fun to read!”

Arita Baaijens (author of Desert Songs: A Woman Explorer in Egypt and Sudan and fellow of the Royal Geographical Society):

“The world could do with a few more female explorers. No one better to lead the way than the undaunted Rosita Forbes. Praise to Margaret Bald for bringing back this great traveler and writer to the spotlight, where she belongs.”

Lord Renton of Mount Harry (nephew of Rosita Forbes and author of Chief Whip: People, Power and Patronage in Westminster):

“From the Sahara to Samarkand not only covers the travels of Rosita Forbes. It reveals the extraordinary courage mixed with knowledge and humour that were keynotes in Sita’s remarkable life. Margaret Bald in her excellent introduction captures with splendid detail Sita’s break from the traditions of “What Women Did” in the 1920s and 1930s. Sita travelled through desert sand by camel or on foot. She visited mosques and temples in dangerous places and met heroes in the process. She wrote with style and beautiful language. Margaret Bald’s introduction, the photo album, and the travel writings themselves are elegant summaries of the splendid diversities in Sita’s life.”

Praise for: The Writings of Rosita Forbes

The New York Times:

“She has an intense and imaginative curiosity about her fellow-humans, makes friends with them everywhere, shares the most appalling living conditions with a gay heart. And she writes of all this with cleverness and a vibrant personal quality of vividness and wit.”

The Times of London (in Rosita Forbes’s obituary):

“She was a keen observer, a shrewd commentator on men and races, and a forceful and interesting writer. Vital, indefatigable, and immensely courageous, she was not only one of the leading women explorers of, at the very least, her own time but one of its most picturesque and entertaining personalities.”

New York Tribune (on The Secret of the Sahara: Kufara):

“By all odds the most absorbing narrative of dangerous adventuring in unknown regions since Shackleton’s ‘South.’ ”

St. Louis Globe Democrat (on Forbidden Road: Kabul to Samarkand):

“…a record of travel and adventure that sparkles with wit and humor, and at the same time throws into relief an intimate and unforgettable picture….”

Peter Fleming (The Times Literary Supplement on Forbidden Road: Kabul to Samarkand):

“Colorful” is the word for her style, but she employs it with considerable skill. Thanks to her powers of observation and to a capacity for letting things happen to her, the story of which she is the not over-obtrusive heroine provides the reader with a picture that is instructive as well as animated.”

Saturday Review of Literature:

“Miss Forbes is one of the most accurate, and incidentally most entertaining of explorers.”

EDITOR’S ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

EDITOR’S NOTE

1919: Into Java and Sumatra

Java

Java and Sumatra

1919: Between Two Armies in China

Southern China

Chin-Chow

1921: The Secret of the Sahara: Kufara

We Enter on the Great Adventure

The Elusive Dunes

1922: An Attempted Pilgrimage to Mecca

An Adventure that Failed

Being the Account of an Attempted Pilgrimage to Mecca

The Pilgrimage Continued

1923: Odyssey in Yemen and Asir

The Odyssey of a Sambukh

Guests of a Hermit Emir

The Menace of a Crowd

1924: Morocco: The Sultan of the Mountains

Into the Days of Haroun Er Rashid

The Wild Land of Raisuli

Raisuli Himself

1925: A Thousand Miles of Abyssinia

Anticipation

The Arks at Harrar

Chiefly Mules and Marriages

The Palaces of Gondar

1928: A Woman with the Legion—South of the Atlas, Morocco

A Woman with the Legion—South of the Atlas, Morocco

1931: Interlude in Turkey, Iraq, and Persia

Veiled and Unveiled Women of the Middle East

Iraq and the Holy Cities of Shia Islam

Interlude in the Anderun

From Isfahan to Shiraz by Motor-Truck

Through the Mountains of Kurdistan

1937: From Kabul to Samarkand

The Nomads’ Road to Kabul

Kabul

In Kandahar

Travelling with Afghans

Bamyan, Valley of the Giant Buddhas

Through the Hindu Kush to Doab

The Glory of Tamerlane

BOOKS BY ROSITA FORBES

ABOUT THE EDITOR

From:

1919

Between Two Armies in China

From Chapters XV and XVI of Unconducted Wanderers (1919)

Southern China

Canton, strangest City in all the world, held us with her lure of wealth and pain, mystery and colour. Once across the canal, which separates the foreign concession, with its neat green lawns and white square houses, from the teeming, age-old native town crushed in between grey crumbling walls, one leaves behind the matter-of-fact atmosphere of the twentieth century, and plunges into scenes that can have changed very little since the days of the Tartar siege.

Down from the wide arcades one steps through a tall gateway into a maze of narrow cobbled streets lined with silent shuttered houses. A Chinese house always has an air of aloof reserve, because it has no windows, and generally a little wall is built across the door, a few feet away from it, to keep out the evil spirits, which can only move in a straight line, and are unable, therefore, to twist round behind the protecting wall!

Canton streets are so narrow that only one sedan-chair can pass through at a time, and even then, in the busy markets, one’s elbows brush bundles of embroidered shoes or strings of fat roasted duck. Above one’s head the dark eaves of the houses almost meet, strips of gay-coloured silk shut out the sun. Carved and gilded dragons adorn the projecting beams of the houses. Scarlet lacquer vies with golden scrolls in profuse adornment of the shops, which are all open to the mellow gloom, and hung with great orange lanterns. Every shop looks like a richly-carved temple, and when one does come suddenly upon a great shrine, guarded by rows of great stone beasts, one is almost disappointed because art can do no more. All the wealth of colour and design has been lavished in the long streets of the silk stores and the jade-merchants, in the market of the singing birds, and even in that dim alley, where the coffin-makers hammer all day at the vast ungainly tree-trunks that the Chinamen buy long before their deaths, and guard jealously in their houses.

Within the great walls of the old city several millions lead their crowded lives, every type of human being jostles his way through the maze of streets: rich merchants sway giddily in cushioned chairs above a pulsating, shouting sea of humanity; fragile pink and white dolls totter on tiny feet leaning on the arm of a silk-clad amah; the golden-robed lama from Thibet pushes aside the beggar, whose sores gleam through indescribable tatters; the pale scholar lifts his long silk coat-tails out of the mire, and the neat black-robed housewife, with dangling jade ear-rings, is elbowed by clamorous coolies monotonously calling, “Hoya, hoya!” as they trot through the dense crowds swinging their burdens from stout poles.

All the spices of the world mingle with the smell of oil and hot humanity; all the colour of the world flows down from the open shop fronts in store of oranges and golden shaddock, in wealth of gorgeous embroidery, in fantastic shapes of jade and crystal, even in massed scarlet cakes and saffron macaroni; all the disease and suffering of the world looks out from under the matted hair of lepers, or from the kohl-darkened eyes of child-women.

It is strange how one can sometimes see the spirits of cities. Bangkok is a dancing girl, shaking a chime of golden bells from her fluttering skirts, dropping perfume from her henna-stained finger-tips; Macao is haunted by the click of high heels, the gleam of dark eyes and a tortoiseshell comb under a dark mantilla, a wistful spirit dragging tired feet through silent deserted streets; but the genius of Canton is something primaeval, fierce and grasping, hiding raw wounds under gorgeous silk, clutching at knowledge and wealth behind a veil that is never lifted.

*****

From Chin-Chow

Chin-Chow, our destination on the Sian river, was in a panic. We came one morning into deserted shuttered streets, and had difficulty in finding an inn at all. Finally we turned two horn-spectacled scholars out of an upper room, looking over the river to a nine-storied pagoda throned high above the town, and modestly furnished with two beds made of boards and covered with thin straw mats. There we fed gorgeously on strange green soup in which floated all sorts of edibles, from macaroni to snails and fishes’ fins, while we watched the hospital boats poling up the river, flying lots of small white flags.

The streets were full of wounded, who lay even upon the temple steps. Flags of the various generals hung in front of the biggest houses. The town had been looted for food and all the shops were shut. Tales of disaster were in the air and rumours of a battle three miles off. Every boat and every chair had been seized for the troops. The last magistrate had fled, because the Southern General had sent in a sudden demand for 30,000 dollars to pay his troops, and his successor of three days was preparing to follow his example, after having beheaded five men in the main street and forgotten to remove the debris.

Some very gallant American missionaries had turned their school, just outside the town, into a hospital, and were struggling with a couple of hundred wounded where they had beds for fifty. They worked in peril of their lives, for the Southerners had massacred the Northern wounded after a recent success, and the North had vowed revenge on the first hospital it captured. The doctor took us all over the hospital where the toy soldiers lay with their rifles under their heads and looks of sullen, mute endurance. Some of them had walked in miles with appalling abdominal wounds, and yet there were very few deaths. The instant a patient was in extremis the orderlies hustled him out into the veranda for fear of his spirit haunting the house. Nearly always, a Chinese is put in the coffin before he is dead, and the instant the last breath is gone the lid is shut down, so that the spirit may not escape and haunt the family.

Sometimes, when this precaution is not taken search has to be made for the spirit with wailing and calling. I’ve heard these cries at night by the river bank after a battle, and it is the most weird, unearthly sound—a long, rising “Kii-ii-rie” that makes one shiver and forget one lives in an electric-lighted, steam-heated age! Often they take the clothes of the dead person and go out searching for his spirit; if they see a little gust of wind whirling some dust into the air, or a dead leaf blown suddenly against a wall, they fling the clothes on top of it and believe they have caught the wandering ghost. One day in Chin-Chow we watched the funeral of a soldier. The immense coffin—a complete tree trunk, painted scarlet at the ends—was borne by some thirty mourners, who danced and shouted, jerked and bumped their burden, waved rattles, and let off fireworks—all this noise to frighten away evil spirits. Theirs is a religion of fear, it seems.

The Confucian code of ethics is little known among the peasants and only a very degraded form of Buddhism is practised. The propitiation of a multitude of spirits and the veneration of their ancestors alone occupies their minds. I was reading an old book of Chinese law once, and I discovered that the penalty for striking an elder brother was strangling; for a woman who struck her husband it was beheading; for killing a husband or father it was “slow death,” which I presume means the death by a thousand cuts. A story that illustrates the extent to which the Chinese carry their veneration of their parents is told in the life of the Emperor Li’. He succeeded to the throne as a child, and his mother, the Empress-Regent, during her son’s absence from the capital, killed his half-brother, the child of the former Emperor’s favourite, and had the woman herself so tortured and maimed that she resembled nothing human, and could only drag herself on the ground. The boy Emperor, returning to his palace, saw the pitiful spectacle, and exclaimed impulsively, “My mother has done wrong!” All the contemporary historians recount this episode, and all of them blame, not the Empress for her cruelty, but the Emperor for criticizing his mother.

*****

Q & A with Margaret Bald, editor of From the Sahara to Samarkand: Selected Travel Writings of Rosita Forbes, 1919–1937

How did Rosita Forbes become famous?

Rosita Forbes first made headlines in 1921, when she survived a four-month expedition by camel to the oasis of Kufara in the Libyan desert disguised as an Egyptian Muslim. For generations, explorers had been tantalized by the idea of reaching Kufara, and the last one who had tried, in 1878–79, had barely escaped with his life. The success of the expedition and the book she wrote about it (The Secret of the Sahara: Kufara)—and the fact that she was young, beautiful, and photogenic—turned her into an instant celebrity. But Kufara was just the beginning for Forbes. She went on to travel the world. She was a widely published journalist and a popular lecturer, and wrote some 30 books between 1919 and 1949.

What inspired her to become an explorer, traveler, and author?

Forbes, who was born Joan Rosita (Sita) Torr in 1890, grew up in a family of landed gentry in Lincolnshire, England. She collected maps and later recalled always longing for adventure, feeling “beset by the need of a destiny,” and inspired by the tales of her Scottish-Spanish grandmother who had crossed the Andes on horseback as a child. Sita Torr’s first opportunity to travel outside Europe came in 1911, when she married a Scottish army officer, Col. Ronald Forbes, and went with him to India, Australia, and South Africa.

When her husband was recalled to London, she pawned her wedding ring and set off alone on horseback to travel among the Zulus. During World War I, having divorced, she volunteered as an ambulance driver in France. After the war, she took to the road again and began to write about her experiences. She said that exploration and travel gave her a sense of purpose and meant liberation from rigid societal conventions and expectations—“no fences, laws or inhibitions,” as she put it.

How did you become interested in assembling a collection of Forbes’s travel writings?

Years ago, when I first began traveling to Morocco, I had read Forbes’s biography of the Moroccan brigand Raisuli in the library and had found aspects of it fascinating. I had seen John Milius’s 1975 film, The Wind and the Lion, with Sean Connery as the Raisuli, which owed a lot to Forbes’s portrait of the Raisuli and her relationship with him. But at the time, I had not realized that she had been an explorer, had traveled so extensively, and had written so many other books.

I enjoy reading travel literature, and looking around on the Internet a few years ago for information on women travel writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, came across mention of Forbes. I did some research, ferreted out copies of her books in antiquarian bookstores, and was astonished by the extent of her accomplishments, the fascinating person she was, and how little known she is today. I was also struck by how insanely intrepid some of her trips were, the splendid style and eloquence of the best of her writing, her sense of humor and zest for life, her insightful reporting, her interest in the lives of women—and particularly in her books about Turkey, Iraq, Persia, and Afghanistan in the 1930s—how relevant her experiences and observations remain today.

Why is Rosita Forbes not as well known today as a travel writer?

The Norton Book of Travel, a massive volume published in 1987, which claimed to collect the best travel writing of the past 2,000 years, included excerpts from the work of 55 writers. Only four were women. Since that time, there has been a revival of the books and the life stories of many women travelers and explorers, particularly those of the 19th century. It has taken even longer to focus on the women of the 1920s and 1930s.

Also, Forbes was multifaceted and prolific, perhaps too much so. In addition to her books, which included novels, history, biography, and memoirs as well as travel, she churned out hundreds of articles of varying quality for U.S. and British newspapers and magazines until the late 1950s, everything from think pieces on international affairs to features on beauty and cooking. Later in her life, she was writing mostly about the Caribbean and the Bahamas, where she had moved, and her greatest adventures had been forgotten. In addition, I think that the glamorous socialite “adventuress” reputation that was born in 1921 lingered on and obscured how serious, courageous, and talented she really was.

What was your biggest surprise in researching Rosita?

I was amazed by how physically arduous many of her journeys were. You can get an idea when you consider the many ways she traveled: crouched on the floor of a Chinese troop train dodging bullets; on a decrepit houseboat poled down a river; by motor car, sedan chair, and pony cart; on foot and on a camel for months in the Sahara and on muleback for months in Abyssinia. She rode half-broken Arabian stallions and horses of every description. She sailed on an overcrowded and sinking Egyptian felucca, on a leaking dhow camped under a piece of canvas for two weeks on the Red Sea, and on the deck of a vermin-infested cargo boat. She rode with the cargo in disintegrating trucks on hair-raising roads in Persia and Afghanistan. She slept on “anything or nothing”—on desert sands, on the ground, in huts, stables, and caves, on tables, rocks, and boat decks, and had to go for months without a bath. A far cry from Eat, Pray, Love.

She epitomized the modern woman of the post-World War I era. Was she considered to be eccentric?

Forbes was always independent and iconoclastic and defied convention in her personal and professional life. She caused a family scandal by divorcing her first husband, whom she said was bad-tempered and unfaithful. She courted gossip by traveling extensively first as an unattached “divorcee” and then without her second husband, Col. Arthur McGrath, to whom she was married for 40 years. (At her wedding to McGrath in 1921, she made headlines when she wore a black wedding dress and carried a walking stick instead of a bouquet.) She was neither a “spinster” nor a mother. She invaded the male preserve of exploration and was a thorn in the side of British colonial administrators, using charm, chutzpah, and her extensive network of establishment connections to get where she wanted to go. And she resisted being pigeonholed and confined by preconceived notions of how she should think and behave.

There was a contradiction between her serious purpose and her celebrity image. How did these two aspects work together?

As much as Forbes benefited in her career from the publicity that chronicled and exaggerated her exploits and focused on her looks—which sold books and tickets to her lectures—she felt frustrated by it. At a time when books and films such as Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik, featuring lecherous Arabs, were all the rage, she said she wanted to correct false Western notions of Arabs. Yet the publicity about her adventures reflected some of the very same “desert sheikh” stereotypes she hoped to debunk. When she lectured about North Africa and the Middle East in 1921, the press was more interested in her black wedding dress than what she had to say about political developments. Although when she was on the road, she often traveled rough, unwashed, with her clothes in tatters, for her public appearances she dressed in Parisian couture, furs, or dramatic hats and was impeccably made up. So she became known as the explorer who traveled with lipstick in place, when nothing could have been further from the truth.

Was it difficult making the selections for the anthology from among so many books—and long ones at that?

The challenge was to select chapters that were interesting and enjoyable to read, would give some of the flavor of her writing, and would stand alone such that readers wouldn’t feel they were missing something. I ended up including excerpts from eight of her books, including her sojourns in Java, Sumatra, and southern China as a naive ingenue from her first book in 1919; the expedition to Kufara; the attempted pilgrimage to Mecca and her trip across the Red Sea to little-known Asir in Arabia and Yemen; travels in Morocco in 1924 and 1928, her thousand-mile expedition in Abyssinia in 1925 to make a documentary film, and the two books from the 1930s on the Middle East and Afghanistan and Soviet Central Asia. What was left out? Her books about South America, the princely kingdoms of India, and the Caribbean. Also the semifictionalized and sensationalized incidents from her travels written for popular magazines, collected in Women Called Wild and These Are Real People, which do not wear well today.

What are your favorite tales of adventure among her books?

The Secret of the Sahara: Kufara is a classic account of desert exploration—of privation, exhaustion, and boredom mixed with moments of terror, elation, and exhilaration. The 1922 story of her abortive pilgrimage from Egypt to Mecca disguised as a Muslim from Adventure, in which she loses her veils while almost drowning in an overturned felucca, is quintessential Forbes. Conflict: Angora to Afghanistan (1931) is a tour de force of reporting and observation at a pivotal time in the development of Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, and Forbidden Road: Kabul to Samarkand (1937) is especially moving in its description of Afghanistan before it was devastated by the decades of war that were to come.

[Link to Margaret Bald’s Amazon Page]

AXIOS PRESS

For Immediate Release

September 1, 2010

Newly Released From the Sahara to Samarkand: Selected Travel Writings of Rosita Forbes (1919-1937)

Author Rosita Forbes was an unabashed feminist at a time when world exploration was a bastion of male privilege

The first anthology of the travel writings of Rosita Forbes, fascinating English writer and explorer

The perfect book for lovers of travel memoirs and exotic adventure

“What an astonishing book this is! Rosita Forbes was not just intrepid but extremely intelligent, not just adventurous but deeply curious, not just a fine writer but a shrewd and sympathetic observer as well. It’s rare to find a person at once so iconoclastic, unconventional and fearless and yet so attuned to her fellow human beings across the globe.”

Rosemary Mahoney, author of Down the Nile: Alone in a Fisherman’s Skiff

In the 1920s and ’30s, the extraordinary Rosita Forbes explored the Libyan desert, sailed across the Red Sea to Yemen, trekked more than a thousand miles into remote Abyssinia, and traveled in Southeast Asia and China, Morocco, Turkey, Iraq, Persia, and Afghanistan. She wrote some thirty books about these and other journeys, was a widely published journalist, a documentary filmmaker, and the editor of a pioneering women’s magazine. Forbes was also a Jazz Age style icon, known as much for her glamour and charm as for her splendid adventures and the engaging and insightful books she wrote about them. This is the first anthology of her travel writings.

Forbes’s travel tales remain fresh and engaging. They are also valuable historical documents. She went to places that would be forever changed by war or revolution and whose histories are central to our understanding of the post-September 11 world. She told her readers what she saw, what she learned, and what it felt like to be there, in her own inimitable style—lively, witty, informative, and opinionated. And she conveyed the moments of terror and tedium, exhaustion and exhilaration, frustration and contentment of life on the road.

For more about the book go to: https://www.axiospress.com/bookstore/from-the-sahara-to-samarkand/

ABOUT THE EDITOR: Margaret Bald is the author of Banned Books: Literature Suppressed on Religious Grounds and the co-author of 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature and 100 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature. She has been a freelance journalist and foreign correspondent, managing editor of World Press Review magazine, and an editorial consultant to the United Nations. She is managing editor at a social policy research organization and lives with her family in Brooklyn, New York.

###

Media Contact

Jody Banks

Axios Press

888-542-9467

[email protected]

Links

[FreePressRelease.com]

[NewswireToday.com]