Summary

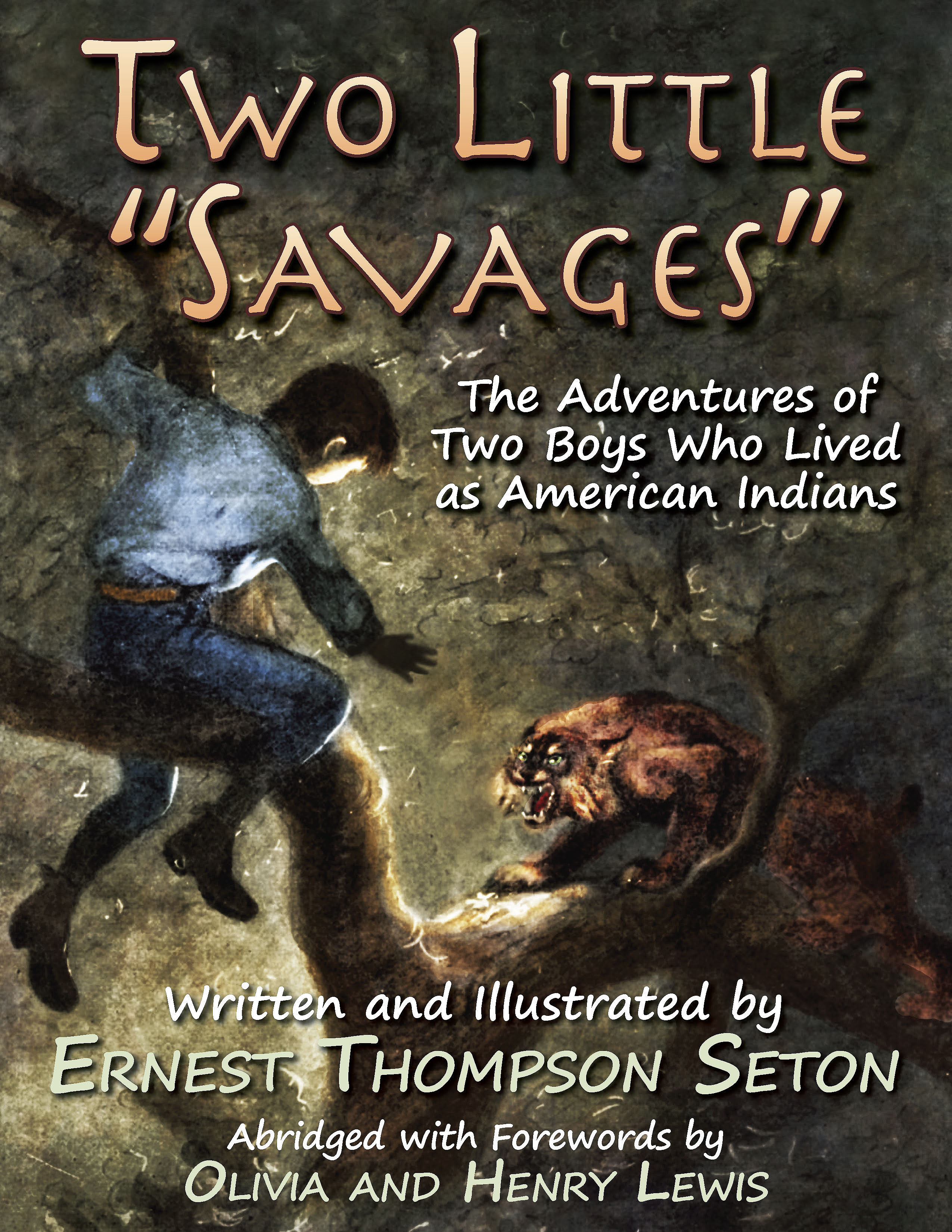

In 1902, Ernest Thompson Seton founded a group called the Woodcraft Indians, whose young members frolicked in war bonnets and camped out in tepees in order to release their “animal energy” and teach them to “think Indian.” He went on to become one of the founding pioneers of the Boy Scouts of America. Although written in the third person, Two Little “Savages” records Seton’s adventures in the woods of Ontario in the summer of 1876, when he and a friend developed games that were later incorporated in Boy Scout rituals still in use today. The book is generously illustrated with over 300 of Seton’s own detailed drawings.

This is one of the great classics of nature and boyhood and presents a vast range of woodlore in the most palatable of forms—a genuinely delightful story. The story concerns two farm boys who build a teepee in the woods and persuade the grownups to let them live in it for a month. The exciting adventures that befall them during their stay in the woods are just the sort of thing that will keep a young reader enthralled and will stimulate the imagination at every turn.

The boys learn how to: prepare their own food, build a fire without matches, use an axe expertly, make a bed out of boughs, “smudge” mosquitoes, get clear water from a muddy pond, build a dam, know the stars, find their way when they get lost, tell the direction of the wind, blaze a trail, distinguish animal tracks, protect themselves from wild animals, and use Indian signals. They also make moccasins, bows and arrows, Indian drums and war bonnets. They discover how to identify the trees and plants and learn all about the habits of various birds and animals including how they get their food, who their enemies are and how they protect themselves from them.

About the Author

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860–1946) was a big man who was known to emit unexpected wolf howls or moose calls in public, and espoused the restitution of the Great Plains to the Indians. He was the author of over seven dozen books, including Wild Animals I Have Known.

_____________

Olivia and Henry Lewis, who abridged the book and wrote the forewords, are sister and brother, and twins. They are just beginning high school in Charlottesville, Virginia.

This illustrated book about the adventures of two boys who lived as American Indians is one of the great classics of nature and boyhood. Two farm boys build a teepee in the woods of Ontario and persuade the grownups to let them live in it for a month. The exciting experiences that befall them will keep a young reader enthralled and will stimulate the imagination at every turn.

The boys learn how to prepare their own food, build a fire without matches, use an axe expertly, make a bed out of boughs, “smudge” mosquitoes, get clear water from a muddy pond, build a dam, know the stars, find their way when they get lost, tell the direction of the wind, blaze a trail, distinguish animal tracks, protect themselves from wild animals, and use Indian signals. They also make moccasins, bows and arrows, Indian drums and war bonnets. They discover how to identify the trees and plants and learn all about the habits of various birds and animals including how they get their food, who their enemies are, and how they protect themselves from them. And the games the boys developed were later incorporated into Boy Scout rituals still in use today.

The book is generously illustrated with over 300 detailed drawings.

FOREWORD: ABOUT THE AUTHOR

FOREWORD: HOW TWO LITTLE “SAVAGES” CHANGED MY LIFE

PREFACE

Part One: Glenyan Yan

1: Glimmerings

2: His Adjoining Brothers

3: The Book

4: The Collarless Stranger

5: Glenyan

6: The Shanty

7: Beginnings of Woodlore

8: Tracks

9: Biddy’s Contribution

10: Lung Balm

11: A Crisis

12: The Lynx

Part Two: Sanger Sam

1: The New Home

2: Sam

3: The Wigwam

4: Caleb

5: The Making of the Teepee

6: The Calm Evening

7: The Sacred Fire

8: The Bows and Arrows

9: The Dam

10: The Hostile Spy

11: The Quarrel

12: The Peace of Minnie

Part Three: In the Woods

1: Really in the Woods

2: The First Night and Morning

3: A Crippled Warrior and the Mud Albums

4: A “Massacree”

5: The Deer Hunt

6: War Bonnet, Teepee, and Coups

7: Campercraft

8: The Indian Drum

9: The Cat and the Skunk

10: The Adventures of a Squirrel Family

11: How to See the Woodfolk

12: Indian Signs and Getting Lost

13: Caleb’s Philosophy

14: A Visit from Raften

15: Sam’s Woodcraft Exploit

16: The Owls and the Night School

17: The Trial of Grit

18: The White Revolver

19: The Triumph of Guy

20: The Coon Hunt

21: The Banshee’s Wail and the Huge Night Prowler

22: Hawkeye Claims another Grand Coup

23: The Three-Fingered Tramp

24: Winning Back the Farm

25: The Rival Tribe

26: White-Man’s Woodcraft

27: The Long Swamp

28: A New Kind of Coon

29: On the Old Campground

30: The New War Chief

INDEX

From Chapter Four: The Collarless Stranger

Each year the ancient springtime madness came more strongly on Yan. Each year he was less inclined to resist it, and one glorious day of late April in its twelfth return he had wandered northward along to a little wood a couple of miles from the town. It was full of unnamed flowers and voices and mysteries. Every tree and thicket had a voice—a long ditch full of water had many that called to him. “Peep-peep-peep,” they seemed to say in invitation for him to come and see. He crawled again and again to the ditch and watched and waited. The loud whistle would sound only a few rods away, “Peeppeep-peep,” but ceased at each spot when he came near—sometimes before him, sometimes behind, but never where he was. He searched through a small pool with his hands, sifted out sticks and leaves, but found nothing else. A farmer going by told him it was only a “spring Peeper,” whatever that was, “some kind of a critter in the water.”

Under a log not far away Yan found a little Lizard that tumbled out of sight into a hole. It was the only living thing there, so he decided that the “Peeper” must be a “Whistling Lizard.” But he was determined to see them when they were calling. How was it that the ponds all around should be full of them calling to him and playing hide and seek and yet defying his most careful search?

The voices ceased as soon as he came near, to be gradually renewed in the pools he had left. His presence was a husher. He lay for a long time watching a pool, but none of the voices began again in range of his eye. At length, after realizing that they were avoiding him, he crawled to a very noisy pond without showing himself, and nearer and yet nearer until he was within three feet of a loud peeper in the floating grass. He located the spot within a few inches and yet could see nothing. He was utterly baffled, and lay there puzzling over it, when suddenly all the near Peepers stopped, and Yan was startled by a footfall; and looking around, he saw a man within a few feet, watching him.

Yan reddened—a stranger was always an enemy; he had a natural aversion to all such, and stared awkwardly as though caught in crime.

The man, a curious looking middle-aged person, was in shabby clothes and wore no collar. He had a tin box strapped on his bent shoulders, and in his hands was a long-handled net. His features, smothered in a grizzly beard, were very prominent and rugged. They gave evidence of intellectual force, with some severity, but his gray-blue eyes had a kindly look.

He had on a common, unbecoming, hard felt hat, and when he raised it to admit the pleasant breeze Yan saw that the wearer had hair like his own—a coarse, Paleolithic mane, piled on his rugged brow, like a mass of seaweed lodged on some storm-beaten rock.

“F’what are ye fynding, my lad?” said he in tones whose gentleness was in no way obscured by a strong Scottish tang.

Still resenting somewhat the stranger’s presence, Yan said, “I’m not finding anything; I am only trying to see what that Whistling Lizard is like.”

The stranger’s eyes twinkled. “Forty years ago Ah was laying by a pool just as Ah seen ye this morning, looking and trying hard to read the riddle of the spring Peeper. Ah lay there all day, aye, and mony anither day, yes, it was nigh onto three years before Ah found it oot. Ah’ll be glad to save ye seeking as long as Ah did, if that’s yer mind. Ah’ll show ye the Peeper.”

Then he raked carefully among the leaves near the ditch, and soon captured a tiny Frog, less than an inch long.

“Ther’s your Whistling Lizard: he no a Lizard at all, but a Froggie. Book men call him Hyla pickeringii, an’ a gude Scotchman he’d make, for ye see the St Andrew’s cross on his wee back Ye see the whistling ones in the water put on’y their beaks oot an’ is hard to see Then they sinks to the bott om when ye come near But you tak this’n home and treat him well and ye’ll see him blow out his throat as big as himsel’ an’ whistle like a steam engine.”

Yan thawed out now He told about the Lizard he had seen.

“That wasna a Lizard; Ah niver see thim aboot here. It must a been a two-striped Spelerpes A Spelerpes is nigh kin to a Frog—a kind of dry-land tadpole, while a Lizard is only a Snake with legs.”

*****

From Chapter Seven: Beginnings of Woodlore

His heart was more and more in his kingdom now; he longed to come and live here. But he only dared to dream that some day he might be allowed to pass a night in the shanty. This was where he would lead his ideal life—the life of an Indian. Here he would show men how to live without cutting down all the trees, spoiling all the streams, and killing every living thing. He would learn how to get the fullest pleasure out of the woods himself and then teach others how to do the same. Though the birds and four foots fascinated him, he would not have hesitated to shoot one had he been able, but to see a tree cut down always caused him great distress. Possibly he realized that the bird might be quickly replaced, but the tree, never. To carry out his plan he must work hard at school, for books had much that he needed. Perhaps someday he might get a chance to see Audubon’s drawings, and so have all his bird worries settled by a single book.

From Chapter Eight: Tracks

In the wet sand down by the edge of the brook he one day found some curious markings—evidently tracks Yan pored over them, then made a life-size drawing of one He shrewdly suspected it to be the track of a Coon—nothing was too good or wild or rare for his valley As soon as he could, he showed the track to the stableman whose dog was said to have killed a Coon once, and hence the man must be an authority on the subject.

“Is that a Coon track?” asked Yan timidly

“How do I know?” said the man roughly, and went on with his work. But a stranger standing near, a curious person with shabby clothes, and a new silk hat on the back of his head, said, “Let me see it.” Yan showed it.

“Is it natural size?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Yep, that’s a Coon track, all right You look at all the big trees near about whar you saw that; then when you find one with a hole in it, you look on the bark and you will fi nd some Coon hars Then you will know you’ve got a Coon tree ”

Yan took the earliest chance He sought and found a great Basswood with some gray hairs caught in the bark He took them home with him, not sure what kind they were He sought the stranger, but he was gone, and no one knew him.

How to identify the hairs was a question; but he remembered a friend who had a Coonskin carriage robe A few hairs of these were compared with those from the tree and left no doubt that the climber was a Coon. Thus Yan got the beginning of the idea that the very hairs of each, as well as its tracks, are different He learned, also, how wise it is to draw everything that

he wished to observe or describe It was accident, or instinct on his part, but he had fallen on a sound principle; there is nothing like a sketch to collect and convey accurate information of form—there is no better developer of true observation.

*****

From Chapter Six: War Bonnet, Teepee, and Coups

“That’s what the Injuns would call a ‘grand coup.’ ” Caleb’s face wore the same pleasant look as when he made the fire with rubbing-sticks.

“What’s a grand coup?” asked Little Beaver.

“Oh, I suppose it’s a big deed. The Injuns call a great feat a ‘coup,’ an’ an extra big one a ‘grand coup.’ Sounds like French, an’ maybe ’tis, but the Injuns says it. They had a regular way of counting their coup, and for each they had the right to an Eagle feather in their bonnet, with a red tuft of hair on the end for the extra good ones.”

“What do you think of our headdresses?” Yan ventured.

“Hm! You ain’t never seen a real one or you wouldn’t go at them that way at all. First place, the feathers should all be white with black tips, an’ fastened not solid like that, but loose on a cap of soft leather. Each feather, you see, has a leather loop lashed on the quill end for a lace to run through and hold it to the cap, an’ then a string running through the middle of each feather to hold it—just so. Then there are ways of marking each feather to show how it was got.”

“Say, boys,” said Yan, “we want to play Injun properly. Let’s get Mr. Clark to show us how to make a real war bonnet. Then we’ll wear only what feathers we win.”

“There’s lots of things we can do—best runner, best Deer hunter, best swimmer, best shot with bow and arrows.”

*****